United We Stand, Divided We Fall

By Reilly Gaunt

Whenever the news mentioned Northern Ireland for about a thirty year period, the country was in a state of political and religious violence.

Currently, Northern Ireland is a land trying to recover from that history of violence and become a place of peace.

A Northern Irish Identity

During a period known as the Troubles, two factions fought over control of Northern Ireland, the Irish Republicans, who were mostly Catholic, and those loyal to the United Kingdom and Britain, who were mostly Protestant.

According to the 2021 Northern Ireland Census, currently 42.3% of people identify as Catholic while 37.3% identify as Protestant. In both cases. Christianity is still the biggest religion in Northern Ireland.

Many people outside the county attribute the fighting to a religious dispute, but the issue ran a lot deeper than just a difference in religion.

Rory Nellis said he remembers the violence in his country when he was a child, but now considers himself a member of a newer, more peaceful generation.

“I’m part of the generation, the first generation. I became 18, I became an adult in a peaceful place,” Nellis said. “I think we’re moving forward now. I think as a city and as a place, I think people are genuinely ready to move on from it.”

Not everybody in Northern Ireland feels as united as Nellis does.

Barbara McDade, a professor at Stranmillis University College in Belfast, said that when she was growing up, often people struggled to define themselves as Northern Irish and instead felt forced to choose a British or Irish identity.

She, like many other students in her generation, chose to leave the country to go to university abroad and away from the violence of the Troubles.

“Majority of people, probably 90, I want to say 95 to 98 percent of the population go into tertiary education, and many of them go into elite universities, either Queens here in the city, or they go across the water to Oxbridge, or to Durham, Edinburgh, St Andrews, that’s my home place, they get to go to some of the most amazing schools in the U.K.,” McDade said.

McDade returned to Northern Ireland after her time abroad, and she said she feels comfortable calling herself both British and Irish.

Other people, like Eevee Steele’s family, still fail to see themselves that way.

“I would say that I am Irish, but not everybody in Bangor would agree with that. It’s quite a Protestant area, so not everybody would feel Irish. Even within my family, there’s people who wouldn’t say that they’re Irish,” Steele said.

Steele, like Nellis, said that this political and religious hesitance is more of a generational divide.

“I can honestly say I’ve never been asked like, which I am. It’s definitely more like the older generation that would care about it. If anyone brings it up, it’s like a joke,” Steele said.

Nellis also said he does not care about the national divide.

“I’m part of a generation, and I think a lot of people of my age and younger, I don’t consider myself either thing,” Nellis said. “I am an Irish man, but I grew up in the United Kingdom. I support an English football team. I watch English TV stations and listen to English radio shows. I also watch Irish ones.”

In Northern Ireland, the younger generations are working hard to leave the turmoil and political divide behind them.

America’s Youthful Perspective

The youth in America say they see something differently happening.

While Northern Ireland seems to be healing from its political wounds from the past, young Americans see the problems as still emerging.

In Northern Ireland, religion and politics came together as two parts of one issue. In America, freedom of religion remains an important part of the country’s national identity. In a 2025 Pew Research Study, 62% of American adults describe themselves as Christian.

But some college students in America say that their country does not keep religion and politics as separate as it seems.

Ruby Kramer, a senior at Indiana Wesleyan University, said that she sees most Americans equate the Republican party as the political group most associated with Christianity. She disagrees with that idea.

“I don’t believe that the ‘Christian Party’ is a thing,” Kramer said. “My family ties religion and politics together, but we let our Christian faith and what God and the Bible teaches us inform our political choices.”

Kramer attends college with fellow senior Matthew Lacy, who shares her ideas on the bond between religion and politics.

Unlike the students in Northern Ireland, Kramer and Lacy attend a private Christian university where they have the option to pursue learning about politics and religion freely. Religion and education are strictly separate in the United Kingdom, and any religious activity cannot be school sanctioned.

“At least with the private Christian institution that we have, there is still space there for diversity of theological belief, diversity of religious practice, which is something I greatly value about my experience at Indiana Wesleyan,” Lacy said. “I’ve met many people who were outside of my specific Christian background, and that has actually allowed me to have a deeper and broader understanding of what it means to be a Christian.”

Other American students, like Shelby Yount, a student at the public University of North Texas, see their schooling directly influenced by the government.

“We’re seeing firsthand with funding cuts and pressure from higher-ups in the college on organizations that are student-led and have nothing to do with the college and pressure from professors to not be politically active or inclined or versed or anything of the sort,” Yount said.

She said that while the younger generations in Northern Ireland are trying to move away from political/religious disputes, in Texas, she sees it growing.

“It feels like Texas Christians are very intolerant of anyone who is non-Christian and they really aren’t interested in evangelizing other people,” Yount said.

In 2025, Indiana University also had massive budget cuts and programs slashed by Indiana Governor Mike Braun.

People like Eevee Steele and Rory Nellis want to take Northern Ireland to a place of peace and prosperity. Students like Kramer, Lacy and Yount say they wish America would follow Northern Ireland’s example.

In two different countries filled with political and religious tension, one appears to be moving forward while the other is just getting started.

Beyond Borders: Landscape, Art and Food

By Mya McNew

Whether the scene is green grassy fields with sheep or rows of corn with fields of cows, St. George’s Market or the James Dean Festival, trying soda bread and chips or the local BBQ joint, they all speak volumes about what defines culture.

Landscape, art and food can significantly highlight aspects of a culture. Northern Ireland and Marion, Indiana, separated by an ocean, hold similarities and differences in how they express their identity with landscape, art and food.

A View Between Villages

Northern Ireland is home to the rocky landscape known as the Giant’s Causeway that stretches four miles along the coast. According to the National Trust, Giant’s Causeway represents love, a legend and world heritage.

Giant’s Causeway still stands at almost 60 million years old, being a historical landscape that shaped the formation of Northern Ireland. Whether to hear the myth of the battle or the myth of the true love story, Giant’s Causeway receives over one million visitors a year.

Corrymeela sits in a small town known as Ballycastle, where the volunteers of Corrymeela provide a community with a safe space. Corrymeela welcomed people from different sides during the Troubles and provided them a way to meet safely, have difficult conversations and support one another.

Elizabeth McKevitt, a Corrymeela Tour Guide, spends time educating visitors on the community of Corrymeela.

“We want to create and shape a culture of generous welcome and acceptance of others. A lot of the feedback we get is the overwhelming feeling of hospitality,” McKevitt.

Corrymeela is known for the peaceful feeling one gets when stepping foot into their community. It provides Northern Ireland communities with hope for what is to come and the sense of peace that all will be ok.

Marion, Indiana, lies in the small Grant County. Marion is home to a vast variety of farmland, along with the school, Indiana Wesleyan University (IWU). IWU provides a greenhouse to support their science courses and the Alliance Garden, which acts as the campus farm.

Jennifer Noseworthy, Indiana Wesleyan Associate Professor of Biology and Division Chair of Natural Sciences, is in charge of the greenhouse and garden, hoping to provide education on the local farmland.

“We use the greenhouse for projects, growing our crops, and starting seeds for the Alliance Garden. Students can get hands-on gardening experiences in both of those places, learning about how plants grow, agriculture, sustainability, and stewardship for the environment,” said Noseworthy.

Gardens of Matter Park, a well-known and often visited park in Grant County, covers 6.3 acres of land. The Gardens of Matter Park provides the Garden House and The Meadow to hold several events like weddings and small concerts, fostering a strong community bond and even shining a light on local artists.

A Communities Canvas

The Belfast Peace Wall continues to stand tall, as many locals believe it will never come down. The Peace Wall’s value remains, as its presence has played a major role in historical events.

The Peace Wall stretches over 21 miles and gets covered in new murals each year. The Peace Wall signifies a sense of hope and artistic freedom/opinion. The wall provides an educational experience on The Troubles for many tourists and has become embedded in the daily life of the Irish.

Dr. Barbara McDade, professor at Stranmillis University, lived through The Troubles and now teaches on the historical facts of Belfast. McDade highlighted the overarching goal for Northern Ireland as time goes on, and the issues that still occur.

“Those are signatures from thousands and thousands of international visitors each year,” McDade said.

Over time, the walls have become taller, stronger and covered in graffiti from locals to present their struggles or beliefs about issues in the city. International visitors sign their names to send signs of hope and prayers, leaving hopeful messages and even verses from the Bible.

Marion also fosters a community in which murals tell historical stories that helped shape and celebrate Marion for the city it is today. Furthermore, downtown Marion holds a place for multiple prominent art groups.

According to The City of Marion, there are nine different artistic organizations based in downtown: Community School of the Arts (CSA), CSA Civic Theater, Creative Hearts Art Studio, Fusion Arts Alliance, Hoosier Shakes, Marion Arts Commission, Marion Design Co., Orchestra Indiana and Quilter’s Hall of Fame.

Festivals and markets allow locals to express their identity through their artwork. Located in Belfast, the St. George’s Market takes place on Fridays through Sundays and occurs throughout the year.

Belfast City officials said that Saturday and Sunday are for the craft market where locals sell handmade crafts, flowers, plants, local photography, pottery, glass and metal work while listening to live music. Artists and local musicians like soloist Rory Nellis spend many weekends performing at St. George’s Market.

“I started a solo career, sort of writing and performing songs, both cover versions in bars and clubs and markets and gigs around,” said Nellis.

The James Dean Festival takes place in Fairmount, located in Grant County, and occurs the last full weekend of September. The James Dean Museum, also located in Fairmount, shows that the festival consists of a street fair, vendor booths, rides, entertainment and a car show.

The beauty of art in culture could be that it is never the same and the different art represents a special meaning to each community. Whether it’s a mural, market or festival, cultures thrive on the success of a community.

Food As Culture

Northern Ireland is known for their Guinness beer, soda bread and chips. Many restaurants in Northern Ireland also offer menus for special dietary needs.

According to the National Library of Medicine, menu labeling promotes healthy living and food choices by allowing customers to see clear facts. Covering every dietary restriction may not be easy, plus many travelers wouldn’t think twice about someone who travels with food allergies/sensitivities.

Certain restaurants do offer gluten-free buns, vegetarian options and fry chips in a separate fryer to prevent cross-contamination. In the U.S., this isn’t as common, and when narrowed in on small towns like Marion, it is not common at all to see restaurants working with visitors who have dietary issues.

“I can never fully relax when I’m constantly rehearsing what to say and how not to come off rude or inconsiderate in a culture I don’t completely understand,” said Delanie Mark, a college junior who traveled to Northern Ireland while dealing with food sensitivity.

A culture is molded by the food served within. Northern Ireland not only molds their culture with unique foods but also offers more diet-friendly options.

Marion is known for their BBQ, local pizza joints and Midwest foods. Many locals wouldn’t think twice about someone with food allergies/sensitivities, leaving restaurants in the position to not prevent cross-contamination.

The Fine Line

Landscape, art, and food all sit at the top of the pedestal in culture. People travel the world for the food, the beautiful landscapes, and the art.

The fine line intertwined within each is what truly shapes culture. The world still tilts on one axis while the sky captures the beauty of it all.

Communication Between Cultures, a Personal Travel Essay

By Emily Bontrager

This trip was sold to me as the “perfect first international experience” for a number of reasons. One reason in particular was the fact that Northern Ireland is a primarily English-speaking country where the language barrier is basically a non-issue. But one important aspect of communication that I learned from this experience is that understanding one another is more than just speaking the same language. Northern Ireland is an entirely new culture, where language, subtext, and even slang has developed in an entirely different way. The differences go further than just a different accent, and they hold more significance than an alternative spelling of words. People may talk in similar ways, but it is those same people who shape and change a language, allowing it to evolve and grow as the times change. In the same way older books are written in a different way than modern books that are being published today, language changes in response to culture. Seeing as this is, by definition, a cross-cultural experience, the differences between Americans and people from Northern Ireland go much deeper than the slight differences we can easily pick up on. Two people may say the same thing with different accents, but they could mean two entirely different things. Slight differences should not be written off as insignificant. There is a reason that they are there.

Some of the differences in language in Northern Ireland are simple ones. For example, trash cans are called “rubbish bins” and according to our travel agent, to-go or take out is commonly called “takeaway.” But some of those differences are much larger, and indicative of deeply rooted divisions among people groups. This division was particularly obvious in the town of Londonderry, alternatively called Derry by Catholic Unionists. The name Londonderry is typically used by Protestant Loyalists, and in most of the interactions we had with locals, both sides seemed very passionate about the name of the town. To give greater historical context, Derry is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland, after the capital city of Belfast. Londonderry also saw a lot of the conflict during The Troubles. To this day there are still several memorials in the area in memory of the conflict, including a memorial for murdered children. Many of the houses and apartment buildings from that time period are still intact, some with their original tenants who lived there during the conflict. For the people of Derry, the name of their home represents more than just where they are from. Londonderry is a name that aligns a person with British values and nationalism, highlighting the Ulster-Scots and British family history that is shared by many Protestants. The name Derry on the other hand, is used primarily by a person who not only has a Catholic background, but likely shares in the romantic idea of one day reuniting the Isle of Ireland under one government, despite the fact that Northern Ireland receives a large amount of monetary support from the British Government. Despite the wishful thinking, uniting Northern Ireland with the Republic of Ireland would likely cause a dramatic decrease in the standard of living for citizens of Northern Ireland according to Sky News correspondent David Blevins.

While this explanation may seem a bit strange from an outsider’s perspective, we had the opportunity to talk with people on both sides of the Derry/Londonderry divide. First, before we even traveled to Derry, we spoke to Deirdre Speer-Whyte who works in the Ulster-Scots museum in Belfast. She briefly served in the military and was at one point an archeologist who uncovered several artifacts from World War II. While we knew next to nothing about Derry at that point, and could not ask proper questions about the issue, she did correct one of the other students who pointed to a map in the museum and said “look, that’s Derry!” Like many residents of Northern Ireland with an Ulster-Scots background, Speer-Whyte frequently travels to Scotland and is very proud of her Scottish heritage. She does not support a unified Ireland claiming “we’re too different,” and said she does not agree with putting former members of the IRA in government. Where others praise the Sinn Fein as a diplomatic, non-violent approach to conflict resolution in Northern Ireland, this Speer-Whyte said that those involved in this political party are murderers who are now leading in government positions. Neither perspective is necessarily inaccurate. Many members of the Sinn Fein political party were involved in the IRA to some extent, but depending on one’s perspective, religion, and political leanings, that fact could be taken in two totally different ways.

When we did visit Derry, we stayed mostly on the Catholic and Unionist side, where the “London” in Londonderry was scratched out on most signs, and Irish flags were everywhere. In the same way using the name Derry or Londonderry says a lot about a person’s beliefs, displaying an Irish flag or Union Jack also clearly illustrates what “side” a person is on. It is here that we met our tour guide for our walking tour of Derry, a man who believes that he will live to see a united Ireland. Although he said he was nonreligious, his background was Catholic, like most in that area. To use reporter James Gould’s wording, when someone claims to be atheist, the next question they are usually asked is “are you a Catholic atheist or a Protestant atheist?” One distinct feature of Northern Ireland as a whole and Derry specifically is that people are very segregated by their beliefs. This happened primarily because of The Troubles, and the violence between neighbors that came with it. People began to move away from each other and closer to “their kind” to avoid attacks from the opposing side. Today, while those with different views are moving closer together again, there are still very distinct Catholic or Protestant areas.

While people in Northern Ireland are very welcoming, there are still a few word choices and phrases that hold historical significance tourists may not be aware of. Even for reporters, the differences in names can pose a unique challenge. David Blevins said that he will switch between saying Derry and Londonderry in his reporting in an attempt to remain objective as a journalist whenever he is reporting in the area. In every culture we assign meanings to words, and a lot of the time what we say has a bigger impact than we may realize. Just because we speak the same language does not necessarily mean we can understand each other. The first step to truly understanding a new culture is to acknowledge that just because you did the pre-departure reading does not mean you know everything. The first step to understanding is to listen, and to listen to all sides.

Political Parallels

By Andrew Scalf

Division

Healing from their past, some people in Northern Ireland, still feel political division and seek justice. Marching forward, the U.S. faces its own growing political division with people on both sides fearing the actions of the other.

Drawing similarities, some in Northern Ireland said lessons can be learned.

“We’ve learned many things over the years and we’ve learned to be friendly, to be dignified and to engage. This is what we do,” John Kelly said.

Kelly, a former guide of the Museum of Free Derry, lived through The Troubles of Northern Ireland and saw the violence firsthand.

The Years Post-Troubles

Londonderry, a Northern Irish city with a deep history of oppression, lives in constant reminder of what those in power have done.

Murals line the Bogside, the marshland outside the inner city, picturing the violence and prominent figures that arose from the years of its growing division. One event shown is Bloody Sunday.

A mural in the Bogside of Londonderry depicts a scene from Bloody Sunday. Catholic Priest, Father Edward Daly, is seen waving a white handkerchief to try to stop the firing as a group of men try to bring the wounded John Duddy, aged 17, to safety. Duddy died shortly after.

“My younger brother, Michael Kelly, who was just 17 years old, was murdered that day. And I was there on Bloody Sunday. And I’ve been involved in the Bloody Sunday issue from that day, more or less, due to the fact all our people were innocent,” Kelly said.

Bloody Sunday was the result of British soldiers firing upon and chasing marchers protesting internment. Fourteen men and boys died and 12 were injured. None of the soldiers responsible faced penalties for their actions.

“A lot of these peaceful marches were attacked,” Kelly said.

Some still resorted to violence, joining the terror group of the Irish Republican Army, to fight against British rule and members of the Ulster Volunteer Force, a loyalist terror group.

The division can be traced back hundreds of years to the invasion of the British and influx of Scottish settlers. London-Derry itself was subject to suppression and gerrymandering since the 19th century.

“There was mass discrimination here, and people lived through that discrimination led to day by day, especially in this city here.This is a majority national city, Catholic city, and was totally discriminated against in every respect,” Kelly said.

Londonderry was just one city where people felt division

“My dad grew up in a really rough estate up in Colerain, and they were kind of the only family that didn’t agree with what was going on there. And my dad and his siblings, like, grew up seeing some really horrible stuff,” Evie Steele said.

Steele, born Generation Z, grew up in the time after the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 brought the era of The Troubles to an end.

Hillsboro Castle is where numerous negotiations and deals were made, leading to and including the Good Friday Agreement.

Growing up, Steele said she saw how division is still prevalent through older generations and holidays like the 12th of July.

“You’ll see, kind of in more extreme cases, people burning the Irish flag,” Steele said.

During the near 30 year span of The Troubles, over 3,500 people were killed.

In the 27 years since, the main terror groups have maintained the agreement with minimal violence.

While many are still divided by political opinion, many hold hope for the future of Northern Ireland

The Growing Troubles

Following the 2nd inauguration of Donald Trump, people have spoken out against both the actions of his administration as well as the president himself.

In June, marches took place across the Los Angeles area to protest deportations and raids by Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Trump, responding to the marches, called in the National Guard to maintain the marchers where soldiers fired upon them with rubber bullets. Soldiers also fired upon and detained members of the press reporting on the marches.

Facing moral and legal criticism, the use of force at these marches is one manifestation of growing division in the U.S.

Texas gerrymandering is a recent development, pushed by republican governor Greg Abbot last month, following Trump’s claim that Republicans deserve five more seats.

Following attempts to redraw districts in Texas, Governor Mike Braun of Indiana announced Vice President JD Vance would visit Indiana to promote further gerrymandering.

In response, democrats are attempting to halt the redrawing of districts and threaten to redraw their own maps.

“I just think people can’t get along. I think people can sometimes get too stuck in their ways or be too focused on one thing that they can’t see the bigger picture,” Keyton Tipple, an IWU sophomore said.

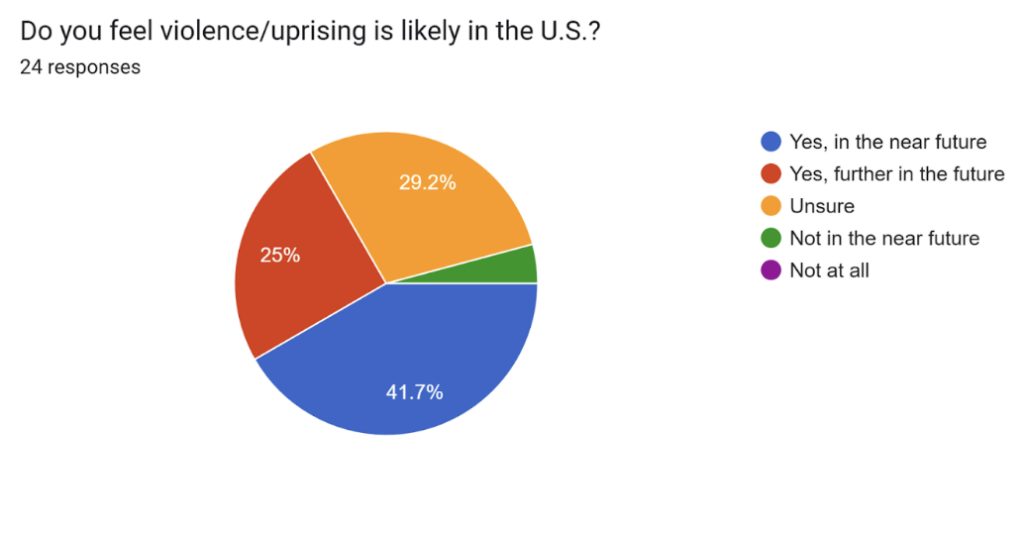

When asked in an independent study if violence or uprising was likely in response to growing tensions, 69.5% of Gen Z said violence is certain. Of those, 62.5% said that violence is coming sooner rather than later.

Data taken from a survey completed August 8. Ninety-five percent of participants were from Generation-Z.

“I would not be surprised if we were to see the same level of violence we saw in the early 2020s in the next three to five years,” Tipple said.

A survey done by YouGov in June of this year found that a majority of U.S. adults said a civil war in the next decade is at least somewhat likely.

“Unfortunately, I do fear that (civil war) is probably going to happen,” Alexa Myers said.

Myers, a recent Oak Hill graduate, said she feels there’s too much emphasis on emotion over logic, leading to violence.

“America has been divided multiple times in the past, history has proven that. And I feel like we haven’t really had a great example of our country at times,” Myers said, “There’s been times history has remade itself and violence tends to be the number one seam that gets repeated.”

Tipple said he could see military involvement and riots in larger urban areas, just not in Grant County.

“From my time of living in Grant County, I haven’t seen much. I don’t think we’re going to see it in small towns or cities like Muncie, Marion, or Gas City,” Tipple said.

Myers disagrees.

“I look at Grant County and I see a very private, close-knit community, but then I also see us as a community where there are a lot of opinionated people. Say we were to have a civil war in our country, I think we would also have a smaller, mini war, in our own county,” Myers said.

Holding various political beliefs and predictions, the commonality of Generation Z is the uncertainty in the future of the U.S.

Outside Perspective

Many from Northern Ireland follow American politics and news, pointing out similarities and offering criticism.

Paul Clark, a news reporter for UTV Live, said media literacy is a major issue in the U.S.

“There’s a blurred line between the journalists and the commentator in America, you know, and we have that here, too,” Clark said.

Clark criticizes leaders of both nations, and said they do not help differentiate between journalism and commentary.

“So you get the basic details, but you also get somebody with an authoritative voice saying their opinion, as if it’s fact,” Clark said.

Others point to lessons from history to better handle the future.

“Well, it’s important, because people must learn from our story, and hopefully it will never happen again. The brutality of the day (Bloody Sunday), the brutality of the following years, right through the conflict, and the fact of what people were actually striving to achieve during those years,” Kelly said.

Military equipment used during the Troubles is displayed at the Museum of Free Derry. Rubber bullets and tear gas were commonly used alongside other weaponry.

The Free Derry Museum builds on Kelly’s words, pointing to where they deem lessons need applied. Currently above the main exhibit, a second exhibit for Palestinian is in place.

“We are prepared to face any sort of injustice that comes our way, and that’s why we will support different campaigns and what’s happening around the world where injustice seems to be instructed on people,” Kelly said.

Deidre Speer-Whyte, of the Ulster-Scots museum, said she believes it’s possible for division to exist with peace.

“I’m not saying that the people who would regard themselves as the other side to me are evil, but we have different ways of looking at the story,” Speer-Whyte said.

Younger generations of Northern Ireland said avoiding identity in opposing sides is better to help move forward.

“We were kind of just in the middle of just, kind of like, you just exist. And we didn’t really get like, either side. But now that I’m older and I’m not living at home as much of the time, like, I find that I’m kind of getting more into that and, like, appreciating it a lot more,” Steele said.

Young and old, the Northern Irish continue offering their outside perspective to the world to try and prevent pain and history from repeating.